Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (b. 1881 – d. 1955)

This article is taken from a 4-part eLearning series, Visions of a New World, that highlights the philosophical perspective, spiritual heart, and cultural context of the lives and work of four contemporary philosophers and mystics Teilhard de Chardin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Vimala Thakar, and Abraham Joshua Heschel. Each has a powerful and unusual way of seeing the world and of articulating higher human potential. You can register for the series at the bottom of this page.

The joy and strength of my life, will have lain

in the realization that when the two ingredients—

God and the world—

were brought together

they set up an endless mutual reaction,

producing a sudden blaze of such intense brilliance

that all the depths of the world were lit up for me.

A Sudden Blaze of Intense Brilliance

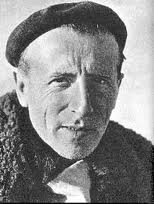

It’s hard to know where to begin to share my admiration and affection for the chiseled-featured field scientist Teilhard de Chardin. The more I read his work, the more astounded I am by his rare heart and unbridled conviction in our human purpose.

It’s hard to know where to begin to share my admiration and affection for the chiseled-featured field scientist Teilhard de Chardin. The more I read his work, the more astounded I am by his rare heart and unbridled conviction in our human purpose.

A seer ahead his time, Teilhard experienced a kind of quiet awakening, a vision of the possible, in the midst of the most unlikely circumstances. From the trenches of WWI, he began to see a grand order to life. In his mind’s eye, he began to see a conscious evolution, a great march towards higher orders of consciousness, higher orders of integration of the human heart and mind. He described what he perceived as a divinization of matter and a progression of life towards greater and greater sanctity.

The mystical milieu is not a completed one in which beings, once they have succeeded in entering it, remain immobilized. It is a complex element, made up of divinized created being. We cannot give it precisely the name of God; it is his Kingdom. Nor can we say that it is; it is in the process of becoming.

What Wonder! This Vision of the Possible

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin tracked an evolutionary current. His work as a paleontologist put him in touch, quite physically with history  writ large. And his active and living spirituality was deeply mystical. For the most part, he spent his intellectual life reconciling these two.

writ large. And his active and living spirituality was deeply mystical. For the most part, he spent his intellectual life reconciling these two.

As he wrote,

“There is a communion with God and a communion with earth, and a communion with God through earth.”

From this probing mind and awakened heart came a body of reflections that bring alive a wondrous evolutionary aspiration for mankind.

Briefly put, de Chardin saw the world as more than material evolution. He saw our interiors as capable of the same creative expanding process. Just as organisms evolved from the simplest single-celled creatures to more complex unions of multi-celled creatures made up of differentiated parts that work in perfect union with each other, so too the human family, Teilhard believed, can evolve to more complex and perfect expressions of harmony and differentiation. More perfect expressions of love. The Omega point, a term he coined, represents a pull from the future. A higher order potential of Love exerting its tractor beam on the present.

Though the future holds out possibilities of greater and greater perfection in a spiritual sense, Teilhard also saw divine Love as perfect in the present. We are all held, he would write, in a Divine Milieu. The context of our present is sacred, and in that sacredness—with all the room for imperfection and development—is a mysterious wholeness that in its largest sense could never be incomplete.

The World in Teilhard’s Times

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was a visionary, who peered out beyond his times. What he began to write about in the first half of the 20th century emerged more articulately in the decades that followed his death. Reading him now, I find it hard to grasp how prescient his work was and what an unusual being he was able to think and care for the unknown future as he did.

Teilhard was born in 1881 to a world before the Brooklyn Bridge or the Statue of Liberty had been built. He died the same year as Einstein, living through an era where the solidity of space and time was challenged by the new physics of relativity. He served as a medic on the frontlines of WWI, a position that thrust him directly into the naked suffering man can inflict on fellow man. They tried to honor his heroism and compassion by moving him up in the ranks and out of harm’s way but he preferred to stay with the troops. At night, unable to sleep, and perhaps propelled by the immediate possibility of life cut short, he began writing essays on an evolutionary understanding of Spirit. What emerged was not a science of despair, but a deeply positive transmission of a creative direction and order to the unfolding universe.

Teilhard was born in 1881 to a world before the Brooklyn Bridge or the Statue of Liberty had been built. He died the same year as Einstein, living through an era where the solidity of space and time was challenged by the new physics of relativity. He served as a medic on the frontlines of WWI, a position that thrust him directly into the naked suffering man can inflict on fellow man. They tried to honor his heroism and compassion by moving him up in the ranks and out of harm’s way but he preferred to stay with the troops. At night, unable to sleep, and perhaps propelled by the immediate possibility of life cut short, he began writing essays on an evolutionary understanding of Spirit. What emerged was not a science of despair, but a deeply positive transmission of a creative direction and order to the unfolding universe.

Upheaval and uncertainty characterized the cultural climate during his life. These were times of accelerating social and global churn. Teilhard watched with hope as the great socialist revolutions rose. Then tragically failed. He was stationed in Peking when the US dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1955, the year Martin Luther King led marchers in Montgomery, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin passed from this world.

Out on the Edge

The key elements of Teilhard’s philosophy point towards a new spiritual view of humanity’s evolutionary potential and to a new values hierarchy. We find echoes of de Chardin’s thinking in the sensibilities of today’s environmentalists, cosmologists, historians, developmental psychologists, and technologists.

This Jesuit’s sense of a single living consciousness, his “noosphere” is often likened to the internet. His non-separation of the spiritual and the material underlies so much of the “spiritually independent’s” thinking. His awareness of our profound interconnectedness—one planet, one biosphere—is all too obvious to environmentalists and climate change activists. His intuition of an evolving consciousness, of a creative process that we can contribute to, resonates with themes explored in neuro-scientific research as well as transformational coaching.

Even in this century, men are still living as chance circumstances decide for them, with no aim but their daily bread of a quiet old age. You can count the few who fall under these spell of a task that far exceeds the dimensions of their individual lives. . . . After having for so long done no more than allow itself to live, Mankind will one day understand that the time has come to undertake its own development and to mark its own road.

A Brief Look At de Chardin’s Life

Pierre Marie Teilhard de Chardin was the fourth of eleven children, born into a happy home in the south of France. He loved the  outdoors, hunting for arrowheads and fossils, and writes of many happy and wholesome times. Drawn to the seminary early in his life, he was also always a scientist at heart. In combination with his theological studies he pursued a degree in paleontology. Though we are more familiar with his philosophical work, Teilhard led a distinguished scientific career, with eleven volumes of strictly scientific writing, several seminal discoveries, and decades in Egypt, China, and Mongolia in the field.

outdoors, hunting for arrowheads and fossils, and writes of many happy and wholesome times. Drawn to the seminary early in his life, he was also always a scientist at heart. In combination with his theological studies he pursued a degree in paleontology. Though we are more familiar with his philosophical work, Teilhard led a distinguished scientific career, with eleven volumes of strictly scientific writing, several seminal discoveries, and decades in Egypt, China, and Mongolia in the field.

In 1905, he journeyed to Cairo on a geological expedition. Six years later, Henri Bergsen’s book Creative Evolution gave him much to consider. Evolution began to haunt his “thoughts like a tune” before WWI, but it was his time on the front that solidified his whole system view and sense of evolutionary unfolding.

Undoubtedly it was during my wartime experience that made me aware of this still relatively rare faculty of perceiving, without actually seeing, the reality and organicity of large collectivities, and developed it in me as an extra sense.

In 1923, after appraising fossils from the Mongolian Steppe, Teilhard set off to Tientsen China to work in the field. The highlight of this period was the great discovery of a Paleolithic skull, indicating inhabitation previously unseen in this part of the world. Teilhard was seminal in dating and evaluating the “Peking Man,” as the remains came to be called. This find, and the work around it, changed our understanding of ancestors’ evolutionary journey populating the globe.

On a philosophical level, he continued to hone his intimations of a “new Christ,” of an evolutionary unfolding. This, not surprisingly, troubled his church superiors at home and in Rome. Teilhard was stretching the limits of doctrine, for he believed,

The world must have a God: but our concept of God must be extended as the dimensions of our world are extended.

The Price of Living At the Edge

de Chardin surfed so far out beyond the edges of the culturally acceptable, especially as an ordained Jesuit priest within a conservative religious order. The church, concerned about his views, forbade him to publish his philosophical thinking in his lifetime. He continued to write, and continued to request permission, but his superiors in France and in Rome repeatedly denied him the freedom to publish and also had him step down from his post lecturing on paleontology and geology his at the Catholic Institute of Paris. The young scientist found this hard.

de Chardin surfed so far out beyond the edges of the culturally acceptable, especially as an ordained Jesuit priest within a conservative religious order. The church, concerned about his views, forbade him to publish his philosophical thinking in his lifetime. He continued to write, and continued to request permission, but his superiors in France and in Rome repeatedly denied him the freedom to publish and also had him step down from his post lecturing on paleontology and geology his at the Catholic Institute of Paris. The young scientist found this hard.

But the loss of his position led to an appointment doing fieldwork in China. He loved, more than anything, being in the field, digging for fossils, and looking into our ancient past. This period in China was perhaps the height of his distinguished scientific career, even while spiritually and emotionally the sting of church’s censure cut deep. A gentle soul, he bore his anguish with grace while in public, but his close friends knew of how much this weighed on him and the sadness and conflict he bore.

A subject that has always been for me the real problem of my interior life. . . . is how to reconcile progress and detachment, a passionate and legitimate love of the earth’s highest development and the exclusive quest for the kingdom of heaven. How can one be as much a Christian as any other man, and yet more a man than anyone?

Without bitterness, rebellion, or malice, de Chardin remained obedient and faithful to his vows, simultaneously he was propelled forward to continue to elaborate on his sense of a Divine Milieu and the evolutionary potential of man. The “possible” called something forth from him. We are all fortunate he could not silence that summons from the future.

Reverence for the Pioneer of Potential

I marvel at this gentle scientist-priest who wove together so many strands of culture and history, matter and morals in his philosophical

skein. Through his books, I’ve grown to love him as a model, a mentor, and a spiritual friend. At times, reading his words, I feel as if he were sitting with me, talking gently in excited tones with a passion for our future, and a loving sensitivity to the mysterious movement of God on Earth.

He also remains to me a man out of time. An enigma. As much as I learn from him, I feel an impenetrable mystery behind his words. It’s the echo of the divine that haunts me most, and I wonder, what threw open the doors of his mind so wide?

Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity,

we shall harness for God the energies of love,

and then, for a second time in the history of the world,

man will have discovered fire.

The spiritual freedom realized by individuals from different cultures gives rise to alternate ways to create a better future. Their profound care and unique expressions fuels our own passion to transform ourselves and the culture we share. In this series, you will meet 4 mystics, each with an inspired heart and far-reaching vision.

The spiritual freedom realized by individuals from different cultures gives rise to alternate ways to create a better future. Their profound care and unique expressions fuels our own passion to transform ourselves and the culture we share. In this series, you will meet 4 mystics, each with an inspired heart and far-reaching vision.

Enter your email, confirm your free subscription, and look for the first installment in your inbox.