This interview with Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi explores his interpretation of views on sexuality and spirituality in Judaism.

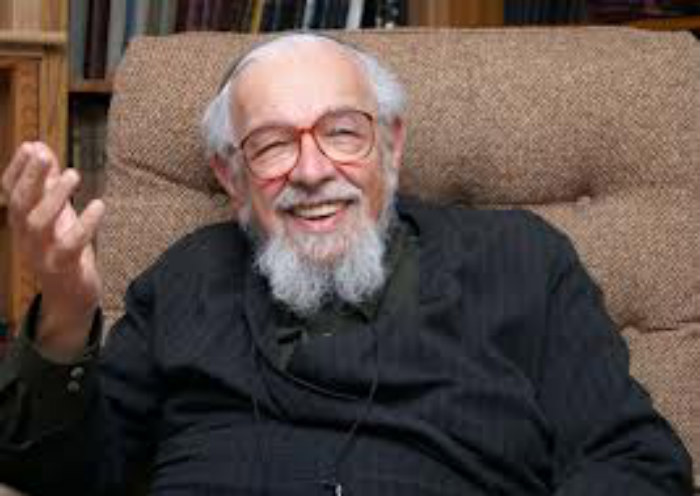

Western tantra, Christian and Hindu celibacy, Tibetan sexual yoga, Buddhist monasticism . . . as we began discussing these vastly divergent approaches to sexuality in spiritual life, I wondered what Judaism had to say about the subject. Raised in a Reconstructionist synagogue with a liberal Zionist approach, I knew, on a cellular level, the importance to Jews of family and children. But were there any teachings on sexuality itself, apart from the all-important injunction that my relatives never cease to remind me of, to be fruitful and multiply? To find out, I called Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi. Rabbi Schachter is renowned for his pioneering efforts to foster interfaith dialogue and spiritual renewal. Ordained as a rabbi in 1947, he is Professor Emeritus of Jewish Mysticism and Psychology of Religion at Temple University and currently holds the World Wisdom Chair at Naropa Institute. Reb Zalman, as he is affectionately known, brought to life for us the captivating Judaic teachings on sexuality.

In our first conversation, he began by saying, “Really, a woman shouldn’t interview a man about these things.” I agreed. Then Reb Zalman surprised me, for he went on to describe a spiritual view on sexual union that was so deeply moving, respectful and explicit that I put down the phone in wonder, having glimpsed, from the picture he had painted, how sexuality could indeed be sacred.

The traditional Jewish teachings are about bringing God into the picture. “Don’t leave God out of it!” Reb Zalman says when he instructs his Bar Mitzvah students about sexuality. Between a man and a woman, specifically a husband and wife, God is made present in their most intimate contact together, and that time is seen as a blessing. Having sex is regarded as a mitzvah, the fulfillment of a divine commandment, and is to be approached as delicately and with as much respect as one would approach any other occasion of worship.

In Judaism, marriage is the threshold to active sexuality. The context is set at the beginning: the blessing uniting the bride and groom begins, “Give great joy to these beloved companions, as you gave joy to Adam and Eve,” and continues, “Blessed are you, Oh Lord, who causes the bridegroom and bride to rejoice in each other.” The couple’s attention is drawn from each other as the source of pleasure to that source which is far greater than any individual, and perhaps most importantly, their sexual delight is sanctified.

Through Rabbi Schachter, I learned of a thirteenth century treatise on sexuality by Rabbi Nachmanides. In The Holy Letter, Nachmanides defines sacred sexuality and the vast difference between experiences of erotic joy within—and outside of—the bounds set in the Torah. He writes: “When a man cleaves to his wife in holiness, the divine presence is manifested. In the mystery of man and woman, there is God. But if they are only aroused, the divine presence will leave them and it will become fire.”

In Orthodox Judaism, detailed prescriptions are laid down for the man, instructing him on how to please his wife. He is meant to give her delight, carefully showing her his affection and desire, so that the woman does not feel unloved, undesired or objectified. When they make love, the husband is instructed to speak gently to his wife, and through his words excite her erotic passion. He should also speak to her about higher matters, lifting her thoughts to spiritual contemplation. The great Rambam [Moses Maimonides, 1134-1204] instructs: “You should first create an atmosphere, speaking to her in a manner that draws her heart after you, appeasing her, making her happy, thus binding her thoughts to yours. It is fitting to say some things that will arouse her and generate love and desire, and some things that will inspire her with awe of Heaven and pious, modest behavior.” And the husband is specifically prohibited from speaking with his wife about other matters during this time, for that will distract them, lessening their arousal and their pleasure. He is even urged to make love with her when he is about to go away on a journey, and again when he returns. Why? Because she will miss him while he is away.

“Is it true that Orthodox Jews have intercourse through a hole in a sheet in order to minimize the erotic experience?” I asked the Rabbi, referring to a tale I had heard from my peers in my Jewish youth group. “Not at all,” Reb Zalman set me straight. “In fact, it’s the opposite. According to the teaching, the couple should be completely unclothed. There should be nothing between them, as there should be no distance between us and God.” What Reb Zalman told me was certainly true. I found a passage from one of the greatest rabbinic commentaries, the Shulchan Aruch, that takes this commandment one step further: “If a man says, ‘I only desire to be intimate while I and she are clothed’—he must divorce her and give her the amount of money specified in the marriage contract. Because the Torah requires specifically that there be physical closeness.”

There is a full-bodied sensuality expressed in Judaism, from the rich melodic prayers taken from the Song of Songs, to the swaying and bowing of fervently praying Jews, to the sweet smell of cloves and oranges at the close of the Sabbath, to the designation of the Sabbath as a specially consecrated time to make love. Practically, the Sabbath eve is a spacious and relaxed time for intimacy—the week’s work is finished and laid aside, the house has been cleaned, meals prepared; the day of rest stretches out before you. Symbolically, the Sabbath is God’s bride. In beautiful imagery and prayers chanted on Friday evening, the devoted worshippers beckon the bride, the Sabbath bride. And likewise, the husband courts his wife, honoring his commitment to her under the marriage contract, and honoring the Sabbath Queen.

These poetic rituals stand as metaphors of the Israelites’ love of God, and at the same time, they seem perfectly designed to address some of the most common, albeit often unverbalized, uncertainties in intimate relationships: How often? When? These questions, potentially a source of anxiety, conflict, miscommunication or projection, are addressed by this body of commandments. The rabbis have even commented on the sheer number and detail of the regulations surrounding sexual intimacy, explaining that these laws are not intended to restrict or prohibit intimate relations but to generate closeness and sanctity in the relationship.

When asked, “Why did the Creator design such an intricate body of law?” One of the rabbinic commentators said: “Because if a husband gets used to his wife through constant contact, he might become disinterested in her. Thus the Torah said, let them be separated for [specified periods] so that she will be as beloved to her husband as she was when she entered the wedding canopy.”

I was struck by the humanity in these teachings, which communicate a very sweet and dignified relationship to sexuality and to one’s partner. Through Judaism’s acceptance and demystification of sexual desire and sexual expression, sex becomes matter-of-fact, simply part of the human experience. And yet, at the same time, with their constant references to that which transcends the participants, the Jewish teachings on sexuality again and again evoke a sense of wonder.

Compared to the detail that the rabbinic commentaries go into regarding the practical meaning of the Torah’s laws for man and woman, not much is written about the more esoteric, mystical view. Yet the Kabbalah [Judaic mystical teaching] does address a transcendent potential in sexual union not unlike that described in Eastern tantric traditions. Not only should God be present in lovemaking, but sexual union itself is seen as a vehicle for transcendence, where the union of husband and wife symbolizes the kabbalistic goal of yichud—cosmic merging. I was intrigued to find that a body of law so precise in its code of ethical conduct also contains a teaching on the dissolution of separate existence and the realization of absolute unity.

Through his personal warmth and effusive nature, Rabbi Schachter himself conveyed much of the spirit and humanity of these teachings. In each of our conversations, he gave generously of his own insights, contemplations and knowledge. His obvious enthusiasm, coupled with evocative traditional commentary, illuminated a broad and multifaceted view on sexuality, leaving us with much to contemplate about the Jewish view on how best to navigate this challenging area of life.

WIE: Since you come from a long line of Hasidim [an Eastern European orthodox sect], I wanted to speak with you about how sexuality is viewed in traditional Judaism. What would you say is the general Jewish perspective on sexuality?

Rabbi Schachter: In Judaism, it is marriage that opens up sexuality as a “yes” after it’s been a “no” for so many years. Marriage is called “kedushin,” which comes from the root word kadosh, meaning holy. In giving the ring, people say, “Harai, at mekudeshet,” which means, “You are consecrated.” So that’s a very, very special attitude.

WIE: How do the rituals surrounding sexuality influence the way the individual would approach this area of life?

RS: Traditionally, the woman wasn’t supposed to invite the man except through looks and gestures. She wasn’t supposed to say anything directly, but when a man saw that she was adorning herself, he had to understand that he was getting an invitation, and he was to act on it. If the man wanted to invite the woman, he might say to her, “Are you ready to do the mitzvah [divine commandment]?” With this attitude, it was both gentle and inviting, and the issue of consent was very important. You will find that to be with a woman against her consent was prohibited. In fact, all the spiritual writers say, “Spend time with her, talk with her beforehand, see that her heart intends to the same thing.” And the model is always, “As God and the divine presence are one, so let us make that kind of union.”

Married sexuality provided laws of family purity that had to be observed. For example, not to have congress during menstruation and so on. And while the Puritans wouldn’t think of making love on the Sabbath, with us it’s the opposite way around. It was considered to be a mitzvah! But you always have to distinguish between whether the setting is kosher or not.

WIE: Is it primarily the setting and the intention that would make sexuality a sacred event?

RS: That’s right.

WIE: Why do you think it is so important in Judaism to make the issue of consent and mutual respect clear?

RS: Do you remember that in the Bible it’s possible to have polygamy? So if a man wanted to marry another woman, the Torah says, the food, clothing and dwelling of the first wife shall not be diminished. Some rabbis say “dwelling” means that she isn’t to be thrown out of her tent, as it were. But other rabbis say no, by “dwelling” it means that if he used to make love with her twice a week, he has to continue to make love with her twice a week. He must not do less now that he has taken another. You see, she is entitled by law to marital congress.

You have another statement from the Talmud [commentary on the Torah] that says, “A person has to honor the wife more than himself.” Or if the wife is of low stature and the husband is tall, it says, “Then bend down to whisper to her. Don’t speak parentally to her.”

WIE: Do you think that these rules are to address the human element in sexual relationships, or do they concern an observant Jew’s relationship with God?

RS: Well, what’s the guarantee that I will do the human thing? Inhalacha [the application of the Torah to everyday living], there is always the question, Why do we do anything? Because this is what God wants us to do. The human considerations don’t come from a mere human situation. Sometimes the man might be angry, or the woman might be angry, and what you want to do at that point is to get to the place where you can restore harmony. The Baal Shem Tov [Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, 1700-1760] says that when a couple has disharmony, they should sit down and read the marriage contract together because it will warm up their hearts.

WIE: It brings God back into view, giving the couple the motivation to work things out?

RS: That’s right.

WIE: It sounds like the traditional teachings say quite a bit about sexuality.

RS: Well, there’s a split. Generally, in the traditional attitudes there is a reluctance to talk about sexuality in a public way, and there’s a wish for great privacy about it. And because of that wish for privacy, there isn’t much written. But if you read Yellow Silk or some of the other erotic Eastern literature you get a sense of how in the East they relish every level of their lovemaking and make it a literary event. At the same time if you read the yogic texts, they also write about their spiritual experiences and where their meditation took them. In Judaism, you find very little of that.

WIE: Why do you think that is?

RS: Because there’s a reluctance to talk about it. It’s almost like saying, “I don’t kiss and tell with God.”

WIE: Do you think the relationship to sexuality becomes more confusing when it’s not spoken about openly?

RS: Yes, especially in our day and age when everything else is put on the table so clearly. I wish that we would have more ecstatic outpourings of the spiritual experiences that people have. And I wish that there were also more outpourings from loving couples sharing with the next generation. You can’t show your child what you’re doing. I can teach my children how to put on tefillin [prayer phylacteries], to wear the tallis [prayer shawl]. But this basic commandment concerning sexuality, I can’t teach them.

WIE: Even though not much is written about ecstatic prayer or about sexuality in Judaism, Jews are a very expressive and sensuous people.

RS: Correct. So this doesn’t mean that you don’t have some kind of a tradition going on despite the fact that the tradition isn’t literary.

WIE: Some spiritual traditions teach that sex is a bad, dirty or evil force. And some traditions teach that it is good, clean and natural, or even more than that, that it is the quickest way to enlightened realization. It seems that Judaism falls into neither category, neither glorifying sexuality nor insisting that it’s a bad thing. Would you say that sexuality is simply an ordinary aspect of life that can be made holy by the way we approach it?

RS: Well, that’s a generalization, and you’ve just got to make sure that you recognize it is a generalization. Because once you start talking about being natural, not being divinely commanded, you’re in a different ballpark. In each religion you will find some people who will be proponents of a holy sexuality, and you will also find proponents of the idea that the whole thing is wrong, it’s bad. It’s not either/or. Also, it depends on what age in history you’re talking about.

WIE: Are there any specific teachings or rabbinic commentaries that help either the man or the woman to better understand the primal nature of sexual desire, the influence it can have over us, and the confusion it can bring?

RS: Well, let’s first begin with the primal question. Of all the 613mitzvahs in the Torah, the very first one is to be fruitful and multiply. It says, “Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother and cleave unto his wife, that they become one flesh.” This mitzvah is primary to any other mitzvah. Now, about your question about confusion—the rabbis say most people have to watch very carefully that they handle their financial situations impeccably because most people run into trouble with that, and only a minority run into trouble with matters of sexuality.

WIE: In the Jewish day schools, or yeshivas, do they teach about the force of sexual desire?

RS: There is no question about that, that’s what they’re obsessed by. Here are people without any outlet during the most active years of their lives. They just don’t go out. They don’t hang out. They don’t stay in the same room behind a closed door with a woman. There are a number of social mores that keep people from excesses. But wherever there is that urge and the will, there sometimes is a way, you know?

WIE: Can you say more about what is studied in the yeshivah?

RS: When I was about twelve years old, I was studying Talmud, and there were questions that had to do with whether a sexual act was consummated or not. This was part of what we were studying in the Talmud, so we dealt with it. We didn’t cover up this material, but on the other hand, we weren’t allowed to do anything about it, you know what I mean? For example, there’s a very clear orthodox teaching that, because of circumcision, the penis is considered to be holy and not to be touched until marriage.

WIE: Because it has been consecrated to God?

RS: That was the basic situation. Because the sign of the covenant has been engraved on it. And traditionally, clearly nothing is supposed to happen before marriage, and masturbation was considered to be a sin.

WIE: Is consecrating the penis with circumcision what makes it a holy object? It seems that this is in accord with the Jewish view that sexuality in and of itself isn’t sacred; the way it becomes sacred is by sanctifying it through prayer.

RS: Correct.

WIE: I know that in the yeshivah there is strong support and encouragement for the boys to devote themselves to prayers and study with great intensity and fervor.

RS: That’s right. And so there is the possibility of either sublimation or early marriage.

WIE: Could another possibility be devotion to an ascetic life?

RS: Well, in some yeshivahs that is the case. When I first studied at the Lubavitch [Hasidic sect founded in the eighteenth century] Yeshivah, a man once came in and said, “Good appetite, boys!” One of us said, “God forbid!” We wanted to eat only for health. There was one guy who would put the salt that the soup needed on the peaches. “I need the salt, but who said it has to come just like my desire is?”

WIE: Were there ever any celibate rabbis?

RS: There were some, and they were looked down on.

WIE: Were there any who were followed in spite of being celibate?

RS: No, we didn’t have that many people in this situation. They were sort of suspect. There was one rabbi way back in the days of the Talmud who, when he studied Torah, was surrounded by fire; they said it was like the angels were around him. His name was Ben Azzai. Ben Azzai said, “I don’t want to be married because my soul yearns for the Torah,” meaning I haven’t got room for a relationship. But by and large, this was very much frowned on. For instance, if someone wanted to be a teacher of children, it was generally understood that unless he was married, you don’t let him do that.

WIE: Why?

RS: Because the way in which they put it, the mothers of the children would come and bring the children, and this was a guy who didn’t have any bread in his basket—I’m giving you the traditional language—so if someone doesn’t have bread in his basket, it wouldn’t be okay.

WIE: Is that because they wouldn’t be fulfilling the laws of the Torah that say one should be fruitful and multiply?

RS: Yes, and also there was the understanding that the urge is so strong that if you don’t have a kosher outlet, then it’s going to drive you to use nonkosher outlets.

WIE: It’s probably true in a lot of cases. Yet, in many of the other spiritual traditions, for example, in Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism, there is a strong celibate tradition.

RS: Yes. And the notion behind many of the Eastern traditions is that semen that is spilled robs you of your kundalini [fundamental vital energy]. This is different in Christianity, in which the notion came from Jesus who said, “Those of you who make yourselves eunuchs for my sake will enter into the kingdom.” During those years all over the Near East, there was a sense that celibacy was a greater way. It is written in the Dead Sea Scrolls that there was a Jewish sect separate from the other sects where they practiced celibacy and only reproduced, as it were, by adopting children. You can read about them in Philo and Josephus.

WIE: What happened to them?

RS: We really don’t know what happened because they had to flee, but one of the things that is very clear is that the early Church Fathers who lived in the desert were an outgrowth of that Jewish group of monastics and hermits. They would have the name of “Abba,” or father. If you read the Desert Fathers, you will see that they are called Abba Peomen, Abba Ephraim and Abba so-and-so. And the women, the great mothers of those times were called “Ima,” or mother.

WIE: That’s fascinating. There was actually an entire ascetic, celibate sect of Jews?

RS: Yes.

WIE: What led them to be celibate?

RS: The notion was that the more life that was brought into the world, the longer it would take for us to clean up the mess of this planet. Remember, even in Judaism there was some idea of original sin because Chapter Three in Genesis is in our Torah. In those years, the thinking was that as much as you can deny the body, the closer you get to God. That was a definition of sainthood that lasted until this century—people would fast and deny themselves.

WIE: Is there within Jewish mysticism any equivalent of sexual tantra?

RS: That’s a situation that I would talk about with some of my male students. A lot of this has to do with intention and with prayer. But the thing that could be said, and that I don’t have to hide, is the attitude of prayer with which people would make love. There was a prayerful attitude in their making love, and they wouldn’t talk but would pray for the next generation that they wanted to bring down. They would pray for each other’s health. So they were in a deep act of prayer.

WIE: Some Western tantric traditions use the time of sexual union to visualize or to pray for something, and in some of the Tibetan practices, one is actually visualizing, during sexual union, ultimate dissolution into emptiness.

RS: In Judaism you have statements like that too. She is supposed to keep in mind the divine name dealing with the Shechina [female principle of God], and he is to keep in mind the divine name of the Holy One, blessed be He. So it’s the male and the female principles. And at the time of their orgasm, they have to just tune into that name.

WIE: Is it supposed to bring you into a meditative realization?

RS: Well, it’s a flip. It doesn’t bring you as you are into the meditative state. It changes you.

This interview with Rabbi Zalman Schachter on sexuality and spirituality was originally published in What Is Enlightenment? magazine in 1997. Reprinted with permission.